GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System)

GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) refers to satellite constellations providing global positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services. It is foundati...

An artificial satellite is a human-made object placed in orbit for communications, navigation, research, and observation, transforming modern life.

Satellites—artificial objects engineered and launched by humans—have become critical infrastructure in the modern world. From enabling global communications and navigation to unlocking the mysteries of the universe, satellites underpin technologies that drive economic growth, national security, scientific discovery, and daily convenience.

Artificial satellites are human-made objects intentionally placed into orbit around Earth or other celestial bodies. Unlike natural satellites (such as the Moon), artificial satellites are designed for specific tasks: broadcasting television signals, providing GPS navigation, monitoring weather patterns, conducting scientific experiments, and supporting military operations. Their construction and operation involve advanced materials and sophisticated subsystems for power, control, data processing, and communication.

International organizations like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) manage radio frequency allocations, orbital slots, and regulatory compliance to prevent interference and promote sustainable use of space.

Natural satellites are celestial objects formed by natural processes that orbit planets or other large bodies. Earth’s Moon is a prime example, as are the dozens of moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn. The primary difference is origin: natural satellites are products of cosmic evolution, while artificial satellites are the result of human design, engineering, and mission planning.

The distinction is fundamental to international space law and operational protocols, as outlined in treaties like the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which sets standards for liability, registration, and environmental responsibility.

The era of artificial satellites began with the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957. This 58-cm sphere, weighing 83.6 kg, transmitted radio signals that were detected worldwide, igniting the “space race.” The United States followed with Explorer 1 in 1958, which discovered the Van Allen radiation belts. The ensuing decades saw rapid advancement:

An orbit is the curved path an object follows around a planet, star, or other body due to gravity. For satellites, orbits are defined by:

Orbits are selected based on the satellite’s mission. For example, Earth observation satellites often use low Earth orbits (LEO) for high-resolution imaging, while communications satellites may use geostationary orbits (GEO) to maintain a fixed position relative to the ground.

A satellite “stays up” by balancing its forward (tangential) velocity with the pull of gravity. At the right speed and altitude, it is in continuous free fall around Earth—falling toward the planet but always missing it due to its horizontal motion. Orbital velocity varies with altitude:

Propulsion systems on board enable periodic adjustments for station-keeping and collision avoidance, as required by international guidelines for orbital safety and debris mitigation.

| Orbit Type | Altitude Range | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Low Earth Orbit | 160–2,000 km | Imaging, Earth observation, LEO comms |

| Medium Earth Orbit | 2,000–35,786 km | Navigation (GPS, Galileo, BeiDou, GLONASS) |

| Geostationary | 35,786 km | TV, internet, weather |

| Sun-synchronous | 600–800 km (typical) | Environmental monitoring, change detection |

| Highly Elliptical | Perigee ~1,000 km, apogee >20,000 km | Science, polar comms, Molniya |

| Polar | Any, passes over poles | Global coverage, mapping, remote sensing |

| Lagrange Points | ~1.5 million km | Deep space telescopes (JWST) |

| Function | Example Missions | Typical Orbits |

|---|---|---|

| Communications | TV, broadband, telephony | GEO, LEO, MEO |

| Earth Observation | Imaging, disaster response, agriculture | LEO, SSO, Polar |

| Navigation/Positioning | GPS, Galileo, GLONASS, BeiDou | MEO |

| Weather | Meteorological, climate monitoring | GEO, LEO |

| Scientific | Astrophysics, environmental studies | LEO, GEO, Lagrange |

| Military/Intelligence | Reconnaissance, secure comms | GEO, LEO, HEO |

| Technology Demonstrators | CubeSats, new sensors | LEO |

Each subsystem is built for redundancy and reliability, following strict international standards (ISO, ITU, ICAO).

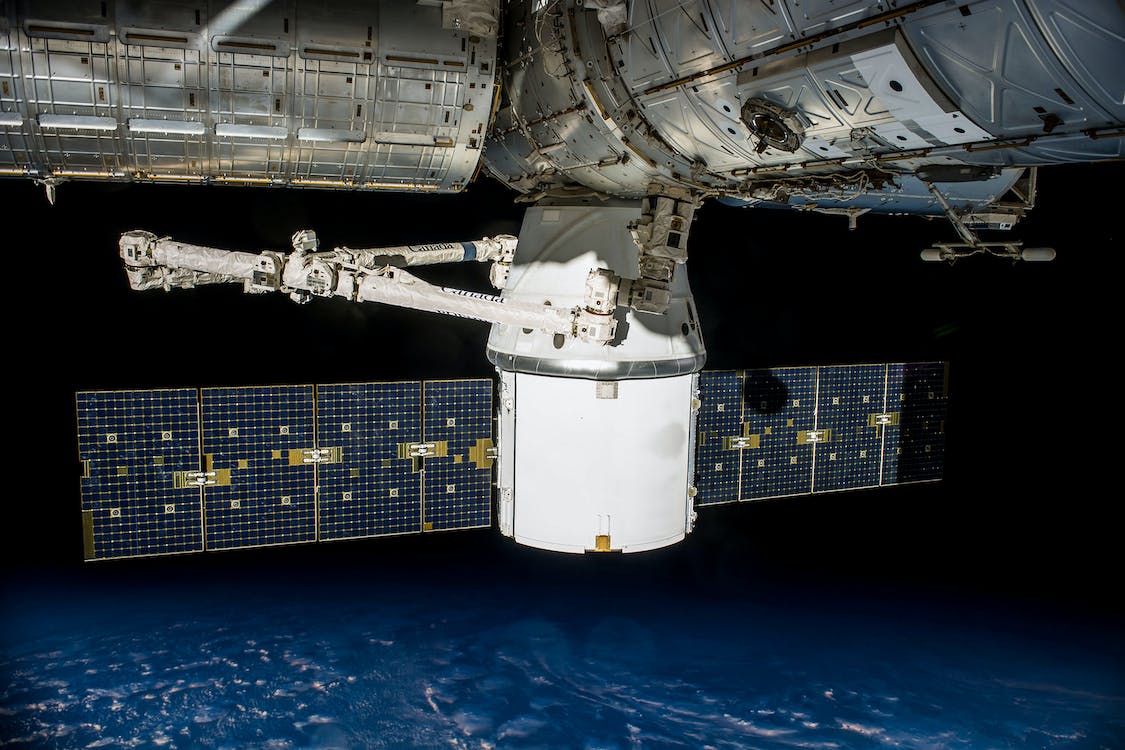

Satellites are powered primarily by solar panels. Image credit: Pixabay/Pexels

Satellites communicate via radio waves, using antennas and onboard transceivers. Frequencies and protocols are regulated by the ITU to avoid interference. Sophisticated encryption and error correction ensure secure, reliable data transmission.

With the proliferation of satellites, orbital debris—defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments—has become a major concern. Collisions can generate clouds of debris, threatening operational satellites and crewed missions. International guidelines (e.g., UN COPUOS, ITU, ICAO) urge satellite operators to deorbit or relocate satellites at end-of-life, minimize debris creation, and adopt active collision avoidance measures.

The limited nature of usable radio frequencies and orbital slots (especially in GEO) requires meticulous international coordination. The ITU allocates frequencies and orbital positions to prevent interference and ensure equitable access for all nations.

Artificial satellites will play an even greater role in global connectivity, environmental sustainability, disaster response, and scientific discovery. Innovations in propulsion, materials, and AI are expanding mission possibilities. Ongoing international cooperation is essential to address orbital congestion, debris, and equitable access, ensuring the sustainable development of the space environment.

Artificial satellites, as technological marvels, have transformed human society—connecting continents, saving lives, and expanding the horizons of knowledge. Their continued evolution will shape the future of science, commerce, and our understanding of the universe.

A natural satellite, such as Earth’s Moon, forms through natural processes and orbits a planet or other celestial body. An artificial satellite, by contrast, is a human-engineered object launched into orbit for specific functions like communication, navigation, or research. Artificial satellites are managed and controlled remotely, while natural satellites follow gravitational paths determined by astrophysical forces.

Satellites stay in orbit by balancing their forward (tangential) velocity with the gravitational pull of the planet they orbit. When launched, they achieve a speed that allows them to continually ‘fall’ around Earth rather than directly back to its surface, creating a stable orbit. The required velocity depends on altitude, with lower orbits needing higher speeds.

The main types include Low Earth Orbit (LEO), Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), Geostationary Orbit (GEO), Sun-synchronous Orbit (SSO), and Highly Elliptical Orbit (HEO). Each serves different mission needs—LEO for imaging and communication, MEO for navigation systems, GEO for fixed-position communications and weather, and SSO for consistent lighting in Earth observation.

Primary subsystems include the structural bus, power system (solar panels and batteries), thermal control, attitude and orbit control, command and data handling, and communications system. Each is designed for autonomy, reliability, and fault tolerance to ensure uninterrupted operation in the harsh environment of space.

Most satellites use solar panels to convert sunlight into electricity, stored in onboard batteries for use during orbital eclipses. Deep-space missions or those far from the Sun may use radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which generate electricity from radioactive decay.

Satellites use systems such as reaction wheels, gyroscopes, magnetorquers, and thrusters to manage their orientation (attitude) and maintain or adjust their orbits. These systems ensure accurate pointing for antennas and sensors and maintain optimal solar panel exposure.

Satellites are used for telecommunications (TV, internet, radio), Earth observation (weather, environmental monitoring), navigation (GPS, GNSS), space science (astronomy, planetary study), military surveillance, and technology testing (CubeSats, new sensors).

As of 2024, over 7,500 active artificial satellites are in orbit around Earth, with thousands more planned in large constellations for global internet coverage and other services.

Orbital debris refers to defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments resulting from collisions or disintegration in space. Growing debris poses collision risks to operational satellites and spacecraft, prompting international efforts for debris mitigation and sustainable space use.

International bodies such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) regulate frequency bands, orbital slot assignments, and cross-border coordination to prevent interference and ensure safe, sustainable satellite operations.

Harness the power of satellites for reliable communications, precise navigation, and advanced Earth observation—improving efficiency, connectivity, and decision-making across industries.

GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) refers to satellite constellations providing global positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services. It is foundati...

Technology is the application of scientific knowledge to create tools, systems, and processes that solve problems or fulfill human needs. In aviation, technolog...

A positioning system determines the precise geographic location of objects or individuals in real time. It underpins navigation, mapping, asset tracking, and cr...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.