Downwind

In aviation, 'downwind' refers both to flying with the wind at the aircraft's tail (tailwind) and to a key leg of the airport traffic pattern. Understanding dow...

A tailwind is wind blowing in the same direction as an object’s movement, increasing groundspeed and affecting safety, performance, and fuel efficiency.

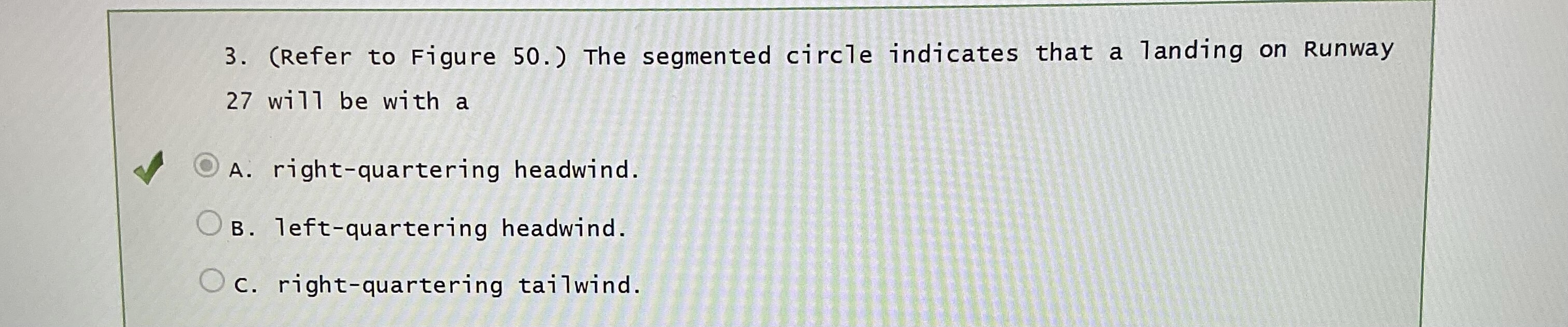

A tailwind is a wind that blows in the same direction as the motion of an object, such as an aircraft, vehicle, or athlete. In both meteorology and aviation, tailwinds have significant implications, influencing everything from travel time and fuel efficiency to operational safety and regulatory compliance.

A tailwind is described in physics through vector addition. For vehicles and aircraft, the speed over the ground (groundspeed) is the sum of the speed through the air (airspeed) and the tailwind component:

Groundspeed = Airspeed + Tailwind Component

If an airplane’s true airspeed is 150 knots and it encounters a 20-knot tailwind, its groundspeed is 170 knots. This principle is fundamental in calculating estimated times of arrival, fuel consumption, and in ensuring safe takeoff and landing.

Tailwinds are not limited to aviation. Cyclists, runners, and vehicles benefit from tailwinds as they reduce resistance and increase efficiency. In meteorology, tailwinds play a role in accelerating weather systems, wildfires, and pollution plumes.

At high altitudes, particularly in jet streams, tailwinds can exceed 100 knots, dramatically affecting long-distance flights. International regulations, such as those from ICAO, require performance calculations to account for wind components during all critical phases of flight.

Meteorologically, tailwinds arise from prevailing wind patterns, local breezes, or jet streams. Wind direction in meteorology is reported as the direction from which the wind originates. A “wind 270°” means the wind is from the west, creating a tailwind for eastbound objects.

Tailwinds accelerate the movement of weather fronts and systems, affecting the timing, severity, and evolution of storms and precipitation. For example, the eastward movement of extratropical cyclones is often hastened by strong upper-level tailwinds such as the polar jet stream.

Meteorological models use tailwind data to predict the dispersion of pollutants, wildfire smoke, and volcanic ash. Ground-based activities, from wildfire response to sea ice drift tracking, rely on accurate tailwind assessments.

In aviation, tailwinds are central to all phases of flight planning and safety. ICAO and regulatory documents require tailwind components to be considered when determining takeoff and landing distances, minimum runway lengths, and fuel needs.

During preflight, pilots and dispatchers review forecast winds along the route, at destination, and alternates. In cruise, strong tailwinds reduce fuel use and save time. For approach and landing, updated wind reports ensure that tailwind limits are not exceeded, especially on short or contaminated runways.

Aircraft have certified maximum allowable tailwind limits, typically 10 knots for commercial jets. Exceeding these limits can invalidate performance calculations, increasing the risk of runway excursions or overruns.

Pilots assess tailwinds through:

For example, if the wind is reported as “210° at 15 knots” and the runway heading is 270°, the tailwind component is:

Tailwind = 15 × cos(60°) ≈ 7.5 knots.

Accurate assessment is vital for safe operations, requiring pilots to monitor rapidly changing conditions and adjust their strategies accordingly.

The tailwind component is calculated as:

Tailwind Component = Wind Speed × cos(θ)

Where θ is the angle between the runway heading and wind direction. If θ > 90°, a tailwind is present; at 90°, it’s a crosswind.

Regulations require pilots to respect maximum allowable tailwind components as specified in the aircraft’s type certificate and standard operating procedures. Exceeding limits can lead to incidents such as runway overruns.

A quartering tailwind approaches from behind and at an angle, creating both tailwind and crosswind components. These are especially challenging during takeoff and landing, as increased groundspeed and lateral drift make control more difficult, particularly for light aircraft or on short, wet runways.

Operators often prohibit or discourage takeoff or landing with significant quartering tailwinds. Accurate calculation of both tailwind and crosswind components is essential for safety.

Tailwinds make takeoff and landing more demanding:

Landing distance required increases by at least 10% for every 2 knots of tailwind (varies by aircraft and conditions). On short, wet, or contaminated runways, tailwind operations are especially hazardous.

Aircraft manufacturers publish detailed takeoff and landing charts factoring in tailwind, runway slope, surface, and weight. Pilots must consult these charts for safe operations.

Tailwinds are most beneficial in cruise, where they:

For example, transatlantic flights from North America to Europe are routed to maximize jet stream tailwinds. However, strong tailwinds can also cause turbulence or early arrivals, requiring coordination with air traffic control.

| Characteristic | Tailwind | Headwind | Crosswind |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind Direction | From behind | From in front | From the side |

| Groundspeed Effect | Increases | Decreases | Neutral |

| Airspeed Effect | Decreases | Increases | Neutral |

| Takeoff/Landing | Longer distances required | Shorter distances required | Requires drift correction |

| Cruise Efficiency | Improves | Reduces | Neutral |

| Operational Risk | Runway excursion, overrun | Stall, climb performance | Loss of directional control |

A tailwind is a wind blowing in the same direction as an object’s movement, increasing groundspeed without increasing airspeed. In aviation, tailwinds are a double-edged sword: beneficial during cruise for efficiency and fuel savings, but hazardous during takeoff and landing, requiring careful calculation and operational limits. In meteorology, tailwinds influence the movement of weather systems, wildfires, and airborne pollutants. Understanding and managing tailwind effects is essential for safety, efficiency, and regulatory compliance across multiple industries.

A tailwind is a wind that blows in the same direction as the movement of an object, such as an aircraft, vehicle, or athlete. In aviation, a tailwind increases the object's groundspeed, which can reduce travel time and fuel consumption during cruise, but requires longer distances for takeoff and landing.

Tailwinds require aircraft to reach higher groundspeeds for takeoff and landing, extending the distance needed to safely leave or touch down on a runway. Exceeding maximum allowable tailwind limits can compromise safety, especially on short or wet runways.

Pilots calculate the tailwind component using the formula: Tailwind = Wind Speed × cos(angle), where the angle is the difference between the runway heading and wind direction. Accurate calculation ensures compliance with aircraft performance limits and regulatory requirements.

A tailwind blows from behind, increasing groundspeed; a headwind blows from in front, decreasing groundspeed but improving lift for takeoff and landing; a crosswind blows from the side, requiring pilots to correct for drift during takeoff and landing.

During cruise, tailwinds increase groundspeed, saving fuel and time. In takeoff and landing, tailwinds require longer runways and reduce braking effectiveness, increasing the risk of runway excursions.

Discover how understanding tailwind components can enhance safety, efficiency, and fuel savings in aviation and other industries. Our experts can help you interpret wind data for better operational decisions.

In aviation, 'downwind' refers both to flying with the wind at the aircraft's tail (tailwind) and to a key leg of the airport traffic pattern. Understanding dow...

A headwind is wind blowing directly towards the front of an aircraft, enhancing lift and reducing ground roll for takeoff and landing. Understanding headwind is...

Wind speed is a key meteorological and aviation parameter, measured at 10 meters above ground for consistency. It determines weather, safety, and operational de...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.