Reactive Power (Q)

Reactive power is the component of AC power that oscillates between the source and reactive elements, essential for voltage regulation and efficient power syste...

Power factor measures how efficiently electrical power is converted into useful work in AC systems. It affects efficiency, costs, and system sizing.

Power factor is a foundational concept in alternating current (AC) electrical systems, reflecting how effectively supplied power is converted into useful work. It is crucial for engineers, facility managers, and utility providers because it directly impacts system efficiency, infrastructure sizing, operational costs, and grid stability.

Power factor is a dimensionless number, ranging from 0 to 1, that quantifies how efficiently electrical power supplied to a circuit is turned into productive work. It is defined as:

[ \text{Power Factor (PF)} = \frac{\text{Real Power (kW)}}{\text{Apparent Power (kVA)}} ]

A power factor of 1 (unity) means all supplied power is used for productive work. Lower values indicate inefficiency, with more energy lost as heat or used to sustain magnetic or electric fields.

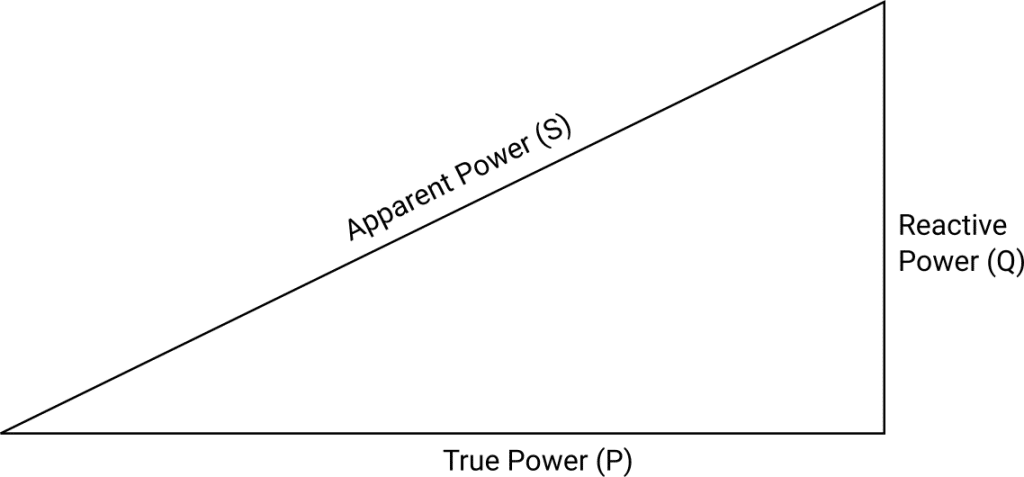

The power triangle visually represents the relationship between real, apparent, and reactive power:

[ S^2 = P^2 + Q^2 ]

The angle between P and S (θ) relates to the power factor:

[

\text{Power Factor} = \cos(\theta)

]

A larger phase angle (greater deviation from in-phase conditions) means a lower power factor and more inefficiency.

Imagine a horse pulling a railcar with the harness at an angle:

If the horse pulls directly forward (power factor = 1), all effort is useful. At an angle, much is wasted “sideways” (lower power factor).

[ \text{Power Factor} = \frac{P}{V_{\text{rms}} \cdot I_{\text{rms}}} ]

High power factor means efficient power usage. Low power factor requires higher current for the same real power, increasing heat losses (( I^2R )), voltage drops, and equipment wear. It also means cables, transformers, and generators must be sized for higher apparent power, increasing capital and operational costs.

Utilities often charge for both real and apparent power. Low power factor results in higher demand charges or penalties, as the grid must be sized for maximum apparent power. Maintaining a high power factor minimizes these costs.

Modern power analyzers, energy management systems, and plug-in meters allow continuous monitoring of power factor, helping to identify and correct inefficiencies.

Factories with many motors, welders, and transformers often have low (lagging) power factor. Correction capacitors are often installed to offset inductive effects and minimize utility penalties.

Offices, malls, and hospitals use motors (elevators, HVAC) and lighting with ballasts, lowering power factor. Centralized or distributed correction is common.

Nonlinear loads such as computers and LED drivers distort current waveforms, lowering power factor. Active power factor correction (PFC) in modern electronics helps meet regulatory standards and improve efficiency.

While most residential loads are resistive, appliances with motors and certain lighting technologies can lower power factor. Residential users are rarely penalized, but collectively these loads can impact grid efficiency.

A manufacturing plant operating motors with a power factor of 0.7 will draw 43% more current for the same real power compared to unity power factor. Installing capacitor banks can raise the power factor above 0.95, reducing current, losses, and penalties.

Energy management systems and modern meters allow real-time power factor tracking. International standards (such as IEC 61000-3-2) set minimum power factor requirements for electronic equipment to ensure grid efficiency and quality.

Power factor is not just a technical metric—it’s a key driver of energy efficiency, cost savings, and system reliability in every AC electrical network.

If you want to optimize your facility’s power factor, boost efficiency, and lower costs, our experts can help design and implement a solution tailored to your needs.

Power factor is the ratio of real power (kW) to apparent power (kVA) in an AC circuit. It indicates how effectively electrical power is being used for productive work. A power factor of 1 means all supplied power is used efficiently, while lower values indicate inefficiency and that some energy is wasted as reactive power.

Low power factor means more current is required to deliver the same real power, which increases system losses, requires larger infrastructure, and often results in penalties from utility companies. It also reduces overall system capacity and can cause voltage drops, affecting equipment performance.

Power factor is commonly improved by installing power factor correction equipment such as capacitor banks, synchronous condensers, or active correction devices. These counteract the effects of inductive or nonlinear loads, reducing reactive power and harmonics to bring power factor closer to unity.

The main causes are inductive loads (motors, transformers), capacitive over-correction, and nonlinear loads (such as devices with switch-mode power supplies or variable frequency drives) that introduce harmonic distortion, all of which reduce the system's true power factor.

Power factor is measured using power analyzers or energy management systems that monitor real, reactive, and apparent power. For complex or nonlinear loads, advanced meters account for both phase shift and harmonic distortion to provide an accurate measurement.

Improve your facility’s power factor to reduce operational costs, avoid penalties, and extend equipment life with expert solutions in correction and monitoring.

Reactive power is the component of AC power that oscillates between the source and reactive elements, essential for voltage regulation and efficient power syste...

A kilowatt (kW) is a standard unit of power equal to 1,000 watts, used globally to measure electrical power in systems from household appliances to aviation gro...

Power consumption is the rate at which electrical energy is used by devices, appliances, or systems. It's key to billing, efficiency, grid management, and susta...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.