Surface

A surface is the two-dimensional outermost extent of an object, central to physics, engineering, and mathematics. Surfaces define interfaces, impact heat transf...

A cross section is the 2D shape formed when a plane slices through a 3D object, revealing internal structure and aiding in analysis and measurement.

A cross section is the two-dimensional shape exposed when a three-dimensional object is sliced by a plane. This concept is deeply embedded in mathematics and the sciences, allowing us to look inside objects and analyze their internal structure—an essential skill whether you’re calculating the strength of a beam, diagnosing a medical condition, or designing a new product. From the growth rings in a tree trunk to the CT scan of a human body, cross sections bridge the gap between what’s on the outside and what lies within.

Cross-sectional analysis is fundamental in geometry, engineering, architecture, medicine, manufacturing, and more. It helps us quantify, model, and understand shapes that would otherwise remain hidden. Cross sections are also central to mathematical methods like Cavalieri’s Principle, which states that solids with equal cross-sectional areas at every height have equal volumes.

A cross section is the intersection of a solid object and a plane. The result is a two-dimensional figure that reveals the internal arrangement and geometry of the solid. The shape and area of a cross section depend on both the object’s geometry and the orientation of the slicing plane.

In calculus, the area of a cross section as a function of position is key to finding the volume of irregular solids. In higher dimensions, the idea extends to slicing 4D (or higher) objects, where the cross section is itself a 3D solid.

Cross sections are everywhere:

Mathematically, cross sections help us:

In projective geometry, cross sections relate to projections and shadows. In topology, slicing higher-dimensional objects with a hyperplane yields cross sections that help us understand complex shapes.

Cross sections serve several purposes:

Any plane slicing a sphere creates a circle (unless it just touches the sphere, in which case the cross section is a point). The radius of the cross-section circle depends on the distance from the center.

A cube can be sliced to produce squares (plane parallel to a face), rectangles, triangles, or even a regular hexagon (with a plane cutting through three pairs of parallel edges).

Slicing a cylinder parallel to its bases yields a circle. Slicing perpendicular to the base through the central axis yields a rectangle. An oblique slice produces an ellipse.

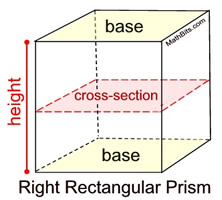

A prism is a polyhedron with two congruent, parallel bases. Slicing parallel to the base yields a cross section congruent to the base. Other slices can produce rectangles, parallelograms, triangles, or hexagons.

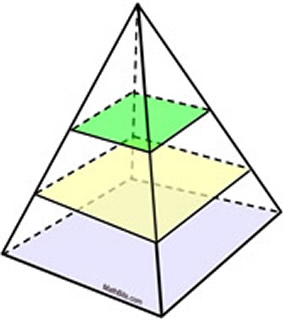

A pyramid with a polygonal base and triangular faces converging at an apex produces similar polygons when sliced parallel to the base. Other slices can yield triangles, trapezoids, or pentagons.

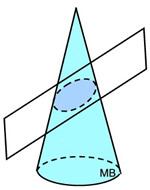

A cone sliced parallel to the base yields a circle. Oblique slices yield ellipses, parabolas, or hyperbolas—the famous conic sections.

A torus (donut shape) can be sliced to produce circles, annuli (ring shapes), or more complex curves depending on orientation.

The orientation of the plane determines the cross-sectional shape:

| Solid | Parallel to Base | Perpendicular to Base | Slanted/Oblique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphere | Circle | Circle | Circle |

| Cube | Square | Square | Rectangle, hexagon, etc. |

| Cylinder | Circle | Rectangle | Ellipse |

| Rectangular Prism | Rectangle | Rectangle | Triangle, trapezoid, etc. |

| Rectangular Pyramid | Rectangle (smaller) | Triangle, trapezoid | Pentagon |

| Cone | Circle | Triangle | Ellipse, parabola, hyperbola |

| Torus | Annulus, 2 circles | 2 circles | Ovals, complex curves |

For polyhedra, a plane can intersect each face at most once—so the cross section of a cube or rectangular prism has at most six sides (a hexagon). For curved solids, cross sections can have infinitely many points (as in a circle or ellipse).

Modeling clay, 3D software, or even slicing fruit can bring cross sections to life. Many educational tools and digital simulators allow you to choose a solid, rotate it, and virtually “cut” it to see the resulting cross section from any angle.

Cross sections unlock the hidden interiors of solids, making them an essential tool for mathematicians, scientists, engineers, and artists. By understanding and visualizing cross sections, we gain powerful insights into the structure, function, and beauty of the three-dimensional world.

In mathematics, a cross section is the two-dimensional shape formed when a plane intersects a three-dimensional solid. It represents the set of points common to both the solid and the slicing plane, revealing the interior features and geometry of the object.

Cross sections are vital for visualizing the internal structure of objects, calculating properties like area and volume, and conducting structural analysis. They are widely used in engineering, architecture, medicine, geology, and manufacturing for both design and diagnostic purposes.

Yes. While some solids produce regular shapes (like circles or squares), others—depending on the object's geometry and the angle of the slicing plane—can yield ellipses, polygons with varying sides, or even more complex curves.

Techniques such as CT and MRI scans create images of cross sections of the human body. By analyzing these slices, doctors can diagnose conditions, plan surgeries, and monitor internal structures in detail.

For polyhedra, the cross section's maximum number of sides is limited by the number of faces of the solid. For example, a cube can generate a hexagonal cross section. Curved solids, like spheres and cylinders, yield cross sections that are curves (e.g., circles, ellipses) with infinitely many points.

Discover how cross-sectional analysis can revolutionize your engineering, design, or scientific projects. Visualize, measure, and optimize structures with precision.

A surface is the two-dimensional outermost extent of an object, central to physics, engineering, and mathematics. Surfaces define interfaces, impact heat transf...

A crack is a physical separation or discontinuity within a material’s structure, often leading to fracture. Understanding cracks and fractures is essential for ...

Computed Tomography (CT) uses multiple X-ray projections and advanced reconstruction algorithms to generate detailed cross-sectional 3D images of internal struc...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.