Deflection Angle

Explore the technical definition, measurement, and application of deflection angle in photometry and aviation lighting. Learn the differences between deflection...

Deflection is the displacement of a structural or mechanical element under load, key to ensuring safety and performance in engineering.

Deflection is the displacement of a structural or mechanical element from its original, unloaded position due to external loads, moments, or its own weight. It’s measured perpendicular to the element’s axis and is a key consideration in engineering design, affecting the safety, serviceability, and performance of everything from bridges and buildings to machine parts and aircraft wings.

Deflection analysis ensures that structural elements do not bend or shift excessively under expected loads. Excessive deflection could result in serviceability issues (such as visible sagging, vibration, or misalignment), damage to finishes or attached elements, or even catastrophic failure.

When loads are applied to beams or structural elements, they deform into a shape known as the elastic curve. The mathematical description of this curve is central to deflection analysis. The curvature at any point along the beam is related to the internal bending moment, the modulus of elasticity (( E )), and the second moment of area (( I )):

[ \frac{d^2v}{dx^2} = \frac{M(x)}{EI} ]

where:

For distributed loads ( w(x) ):

[ EI \frac{d^4v}{dx^4} = w(x) ]

Common assumptions in classical beam theory include small deflections, linear elastic materials, and prismatic (constant cross-section) beams.

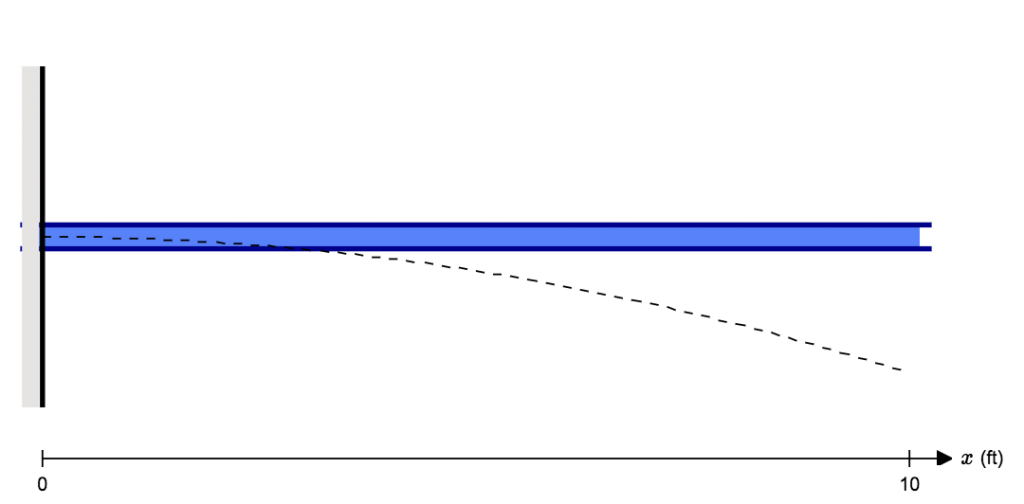

A beam fixed at one end and free at the other.

Point load at free end:

[ \Delta_{max} = \frac{P L^3}{3EI} ]

Uniformly distributed load:

[ \Delta_{max} = \frac{w L^4}{8EI} ]

Pinned at both ends (one pinned, one roller). Common in bridges and floors.

Central point load:

[ \Delta_{max} = \frac{P L^3}{48EI} ]

Uniformly distributed load:

[ \Delta_{max} = \frac{5 q L^4}{384EI} ]

Analysis involves both equilibrium and compatibility (deflection) equations. Common in continuous beams and redundant structures.

Uniform or variable (triangular, trapezoidal) loads require integration or advanced methods for precise deflection calculation.

Integrate the moment-curvature equation twice to find expressions for slope and deflection. Apply boundary conditions (such as ( v = 0 ) or ( \theta = 0 ) at supports) to solve for integration constants.

Relates the area under the ( M/EI ) diagram to changes in slope and displacement between two points. Useful for beams with multiple loads.

For linear systems, the total deflection is the sum of deflections from individual loads acting separately.

Castigliano’s theorem uses strain energy to find deflection at specific points, especially useful for indeterminate structures.

Complex structures and loadings are often analyzed using FEA software, which divides the structure into small elements and solves for deflection numerically.

The way a beam or element is supported governs its deflection characteristics:

| Support Type | Deflection ( v ) | Slope ( \theta ) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | 0 | 0 | Wall/column base, rigid frame |

| Pinned | 0 | Free | Bridge support, truss joint |

| Roller | 0 | Free | Expansion joint, bridge abutment |

| Free | Free | Free | Cantilever tip |

Continuity conditions ensure that deflection and slope are consistent across changes in geometry, materials, or loading.

Given:

Maximum deflection at free end:

[ \Delta_{max} = \frac{P L^3}{3EI} ]

Derivation:

Note: For advanced analysis, especially in aerospace and critical infrastructure, consult relevant codes (e.g., ICAO, EASA, AISC, Eurocode) and employ validated software tools.

Deflection refers to the perpendicular displacement of a point on a structural or mechanical element from its original axis, caused by applied forces, moments, or self-weight. It's a crucial parameter in ensuring that beams, frames, and other structures perform as intended without excessive deformation that could impair function or safety.

Deflection is typically calculated using principles from mechanics of materials, specifically the moment-curvature relationship and differential equations. Analytical methods such as the double integration method, moment-area method, superposition, and energy methods (e.g., Castigliano’s theorem) are common. For complex structures, engineers often use computer-aided finite element analysis.

Excessive deflection can lead to serviceability problems such as cracking, vibration, misalignment, and even structural failure. Limiting deflection ensures structures are safe, functional, and comfortable for occupants or operators, and meets code requirements set by standards organizations and regulatory bodies in fields like civil and aerospace engineering.

Deflection depends on the magnitude, type, and position of applied loads, the length and geometry of the element, support conditions, and material properties—especially Young’s modulus and the second moment of area. Boundary conditions (such as supports or connections) also play a significant role in how much and where deflection occurs.

Deflection is a global measure of the movement of a structure or element as a whole. Stress is the internal force per unit area within a material, and strain is the deformation per unit length. While stress and strain are local properties at a point, deflection describes the overall displacement or shape change of the entire element.

Minimize unwanted deflections in your projects with advanced engineering analysis. Explore solutions for safer, more reliable structures and machinery.

Explore the technical definition, measurement, and application of deflection angle in photometry and aviation lighting. Learn the differences between deflection...

Deformation in physics refers to the change in shape or size of an object when subjected to applied forces. It is fundamental to materials science, engineering,...

A cantilever is a structural element anchored at only one end, projecting into space and supporting loads without direct support at the free end. Common in brid...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.