Measurement Accuracy

Measurement accuracy is the closeness of a measured value to the true value, crucial in aviation, science, and industry. It ensures reliable results, safety, an...

A technical guide to accuracy, precision, repeatability, and reproducibility in measurement—covering definitions, standards, real-world examples, and practical implications.

Understanding measurement quality is essential in fields from aviation and aerospace to pharmaceuticals, automotive, and advanced manufacturing. The terms accuracy, precision, repeatability, and reproducibility form the foundation of metrology, quality assurance, and regulatory compliance. Here, we provide technical definitions, international standards, real-world examples, and the practical implications of these terms.

Definition and Standards

Accuracy is the degree of closeness between a measured value and the actual (true) value of the quantity being measured, called the measurand. According to the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM, ISO/IEC Guide 99:2007), accuracy is qualitative—described as “high” or “low”—and is closely linked to the absence of systematic error or bias.

Accuracy reflects how correct a measurement is. Systematic errors—consistent deviations caused by miscalibration, instrument drift, or procedural flaws—reduce accuracy. Mathematically, accuracy is often represented by comparing the mean value of repeated measurements to a reference standard.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| What it reflects | Closeness to the true value |

| Influenced by | Systematic errors, calibration, reference standards |

| Example in aviation | GPS position, altimeter readings, fuel flow meters |

In aviation, accuracy is critical—for example, in Performance-Based Navigation (PBN), where Required Navigation Performance (RNP) levels specify minimum accuracy thresholds for navigation systems. Calibration of altimeters, ILS, and air data computers ensures compliance and safety.

Definition and Standards

Precision is the degree to which repeated measurements under unchanged conditions produce similar results. Per ISO/IEC Guide 99:2007, it is “the closeness of agreement between indications or measured quantity values obtained by replicate measurements on the same or similar objects under specified conditions.” Precision is about consistency, not correctness.

Precision is primarily affected by random errors—unpredictable fluctuations due to environmental changes, instrument instability, or operator variability. It is quantified using statistical measures such as standard deviation and variance.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| What it reflects | Closeness of repeated measurements to one another |

| Influenced by | Random errors, environmental fluctuations, instrument design |

| Example in aviation | Repeated altitude readings, pressure sensor outputs |

High precision is crucial for quality control and trend monitoring. For example, an aircraft fuel flow sensor that reports consistent readings (even if offset) is highly precise, though not necessarily accurate.

Note:

High precision does not guarantee high accuracy.

Definition and Standards

Repeatability is the degree to which the same measurement process yields the same results when repeated under identical conditions—same operator, equipment, location, and a short time frame (ISO 5725-2).

Repeatability is a subset of precision: it assesses the within-lab, short-term stability of a measurement system. Low repeatability signals issues like mechanical wear or inconsistent procedures.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| What it reflects | Consistency under identical conditions |

| Influenced by | Instrument stability, operator technique, environmental control |

| Example in aviation | Maintenance technician measuring tire pressure with same gauge |

Repeatability is vital in manufacturing and laboratory settings. For instance, repeated thickness measurements of a metal sheet using the same micrometer should yield nearly identical results to qualify the process as repeatable.

Definition and Standards

Reproducibility measures the degree to which consistent results are obtained when measurement conditions change—such as different operators, instruments, locations, or times (ISO 5725-2).

Reproducibility assesses the robustness of a measurement method across variable conditions, crucial for multi-site operations and regulatory acceptance. It is evaluated by comparing results from different labs, instruments, or personnel.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| What it reflects | Consistency under varying conditions (operators, instruments) |

| Influenced by | Equipment differences, operator skill, procedural variations |

| Example in aviation | Altitude calibration checks performed by different teams |

Reproducibility ensures that tests and calibrations performed by different teams or in different locations are reliable and accepted by regulators such as ICAO or EASA.

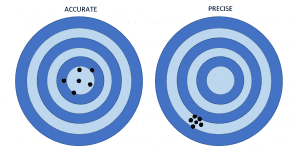

The dartboard analogy clearly illustrates these concepts:

Repeatability is shown by one player throwing from the same spot; reproducibility by multiple players using different darts or positions.

| Error Type | Main Effect | Source Example | How to Minimize |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic | Reduces accuracy | Miscalibrated altimeter | Calibration, maintenance |

| Random | Reduces precision | Sensor electrical noise | Averaging, better sensors |

Calibration aligns instrument readings with known standards, as mandated by ICAO and ISO. It involves comparison, adjustment, documentation, and interval setting based on drift and criticality.

Laboratory Weighing:

Repeatedly weighing a 10.00 g standard on an analytical balance demonstrates accuracy (mean value matches standard) and precision (low scatter).

Industrial Process Control:

Jet engine sensors must provide accurate, precise readings; reproducibility ensures different teams reach the same results.

Manufacturing Quality Control:

Measuring rivet hole diameters—high precision detects tool wear, high accuracy ensures design compliance.

Metrology Labs:

Gage R&R studies quantify repeatability and reproducibility, supporting measurement system reliability.

| Concept | Definition | Main Focus | Example | Improved By |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness to true/reference value | Correctness | Altimeter reads true altitude | Calibration, standards |

| Precision | Closeness of results to each other | Consistency | Multiple airspeed readings aligned | Quality sensors, SOPs |

| Repeatability | Consistent results under same conditions | Short-term stability | Same gauge, repeated by same tech | Standardized procedures |

| Reproducibility | Consistency across different setups | Systemic robustness | Different teams, similar results | Training, calibration, SOPs |

Measurement quality directly impacts safety, compliance, and efficiency:

Accuracy describes how close a measurement is to the actual true value, while precision refers to how close multiple repeated measurements are to each other, regardless of their closeness to the true value. An instrument can be precise but not accurate if it consistently produces results that are offset from the true value due to systematic error.

Repeatability is the consistency of measurements under identical conditions (same equipment, operator, and environment over a short period). Reproducibility measures consistency when conditions change, such as different operators, instruments, or locations. Both are critical for assessing the reliability of a measurement system.

Accurate and precise measurements ensure safety, regulatory compliance, and operational efficiency. In aviation, for example, inaccurate altimeters or imprecise torque wrenches can result in safety incidents or regulatory violations. Robust measurement quality reduces errors, improves product quality, and supports reliable decision-making.

Systematic errors (affecting accuracy) are minimized through regular calibration, maintenance, and use of traceable standards. Random errors (affecting precision) are reduced by improving instrument quality, controlling environmental factors, and standardizing procedures. Measurement system analysis (like Gage R&R) helps identify and address sources of error.

Best practices include scheduled calibration, standardized operating procedures, operator training, environmental control, use of high-quality instruments, and regular analysis of measurement system variability. Maintaining traceable records and adhering to international standards like ISO and ICAO guidelines are also essential.

Ensure safety, compliance, and operational reliability with accurate, precise measurements and robust calibration programs. Discover how our solutions can streamline your quality assurance and compliance processes across aviation, manufacturing, and research.

Measurement accuracy is the closeness of a measured value to the true value, crucial in aviation, science, and industry. It ensures reliable results, safety, an...

Measurement precision defines the repeatability and consistency of measurement results under specified conditions, essential for scientific, industrial, and qua...

Reproducibility and repeatability are pillars of measurement quality, ensuring that data is reliable, comparable, and actionable across industries. Learn how th...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.