Fog

Fog is a surface-based hydrometeor characterized by suspended water droplets or ice crystals near the ground, reducing horizontal visibility to less than 1 kilo...

Haze: fine dry particles in the air that reduce visibility and create a milky, faded look, crucial in aviation and environmental health.

Haze refers to atmospheric obscuration caused by the suspension of extremely small, dry solid or liquid particles in the air, resulting in reduced visibility and a milky or faded sky. Distinct from fog and mist—which are composed of water droplets—haze’s primary constituents are aerosols: microscopic particles or droplets from both natural and anthropogenic sources. In aviation, haze is reported using the code “HZ” in meteorological observations (METAR/SPECI) and represents a significant operational and environmental concern.

Haze is defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as a reduction in horizontal visibility caused by suspended, dry particles too small to be seen individually. These particles—ranging from 0.001 to 10 micrometers (µm)—come from dust, combustion byproducts, sulfates, nitrates, sea salt, organic matter, and black carbon.

Core features:

Haze results from a complex mix of fine aerosols in the lower troposphere. These include:

Water absorption: Many haze particles are hygroscopic, swelling and scattering more light at relative humidity above 60–75%. This explains why haze can intensify during humid periods, even in the absence of new particle emissions.

Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD): A key metric for haze, AOD quantifies the column-integrated concentration of aerosols. High AOD values indicate severe haze and low surface visibility.

Haze forms and persists through a combination of emission, transport, chemistry, and meteorology:

| Phenomenon | Primary Composition | Particle Size | Water Content | Visibility Reduction | Humidity for Formation | Appearance | Key Distinction from Haze |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haze | Dry aerosols | 0.001–10 µm | Low | <10 km, >1 km | >60–75% (for swelling) | Milky, faded | Dry, not water droplets |

| Fog | Water droplets | 1–10 µm | Very high | <1 km | 100% (saturated) | Thick, white | Liquid droplets, dense |

| Mist | Water droplets | 1–10 µm | High | 1–10 km | 95–100% | Gray, thin | Water-based, less dense |

| Dust | Mineral particles | 1–100 µm | Very low | Variable | Dry, windy | Brown/yellowish | Larger, visible grains |

| Smoke | Combustion aerosols | 0.01–1 µm | Low | Variable | Dry | Blue-gray/brown | Combustion source |

Haze is unique for its composition of sub-micron to micron-sized dry particles, not visible individually, and its ability to reduce visibility by scattering light. Fog and mist are water-based; dust and sand involve larger, visible particles; smoke arises from combustion.

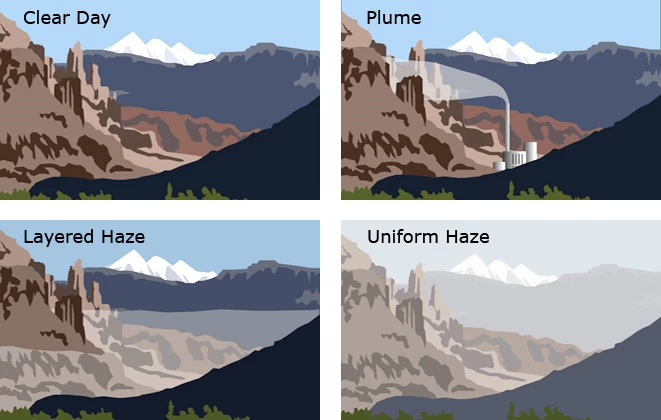

Haze dramatically reduces visual range, impacting transportation and aesthetics:

National parks like the Grand Canyon and Great Smoky Mountains experience dramatic visibility loss from haze, reducing views from over 100 miles to under 20 miles.

Forest and peat fires in Indonesia can produce transboundary haze, impacting air quality and transportation across Southeast Asia. Severe events close airports, disrupt shipping, and create public health crises.

Major eruptions (e.g., Kīlauea, Eyjafjallajökull) inject ash and sulfate aerosols, creating regional or global haze that can persist for weeks to months.

Cities such as Los Angeles and Beijing experience photochemical haze events from vehicle and industrial emissions, sunlight, and atmospheric inversions—causing severe visibility reduction and health risks.

Haze is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon with critical impacts on transportation, health, environment, and climate. Its monitoring and mitigation are central to aviation safety, air quality management, and preserving the natural beauty of landscapes worldwide.

Haze consists of dry, fine particles (aerosols) that scatter light, reducing visibility and giving the sky a faded look. Fog, by contrast, is made up of suspended water droplets and requires near-saturation humidity, resulting in much denser obscuration and typically lower visibility (<1 km compared to haze’s >1 km).

Haze reduces horizontal visibility, especially near the surface, making it harder for pilots to see runways, terrain, and other aircraft. It is reported on METARs as 'HZ' and can lead to missed approaches, diversions, and increased reliance on instruments, particularly under Visual Flight Rules (VFR).

Haze forms from a mix of natural and human-made aerosols, such as mineral dust, sulfates, nitrates, sea salt, organic compounds, and black carbon. These particles scatter sunlight, and their concentration increases with emissions, transport, and atmospheric stagnation. High humidity can amplify haze by causing hygroscopic particles to swell and scatter more light.

Haze is tracked using ground-based visibility observations, transmissometers, nephelometers, and satellite remote sensing (e.g., MODIS, CALIPSO). In aviation, haze is formally reported as 'HZ' in METAR and SPECI codes when visibility reduction is due to dry particles rather than water droplets or precipitation.

Fine particles in haze (especially PM2.5) can penetrate deep into the lungs, aggravating respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, and increasing the risk of heart attacks, strokes, and premature death. Vulnerable groups include children, the elderly, and those with chronic health conditions.

Stay ahead of visibility challenges with advanced haze monitoring and reporting. Learn how our solutions can help pilots, dispatchers, and environmental professionals manage haze impacts.

Fog is a surface-based hydrometeor characterized by suspended water droplets or ice crystals near the ground, reducing horizontal visibility to less than 1 kilo...

Obscuration is a meteorological term for any atmospheric phenomenon, other than precipitation, that reduces horizontal visibility. It is crucial for aviation sa...

Low visibility in aviation describes conditions where a pilot's ability to see and identify objects is reduced below regulatory thresholds, impacting critical p...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.